- Home

- Services

- Constructive Dismissal

- COVID-19

- Discrimination / Human Rights

- Employee Sued by Employer

- Employment Contracts: Drafting / Review / Negotiation

- Employment Policy Drafting / Review

- Fiduciary Obligations

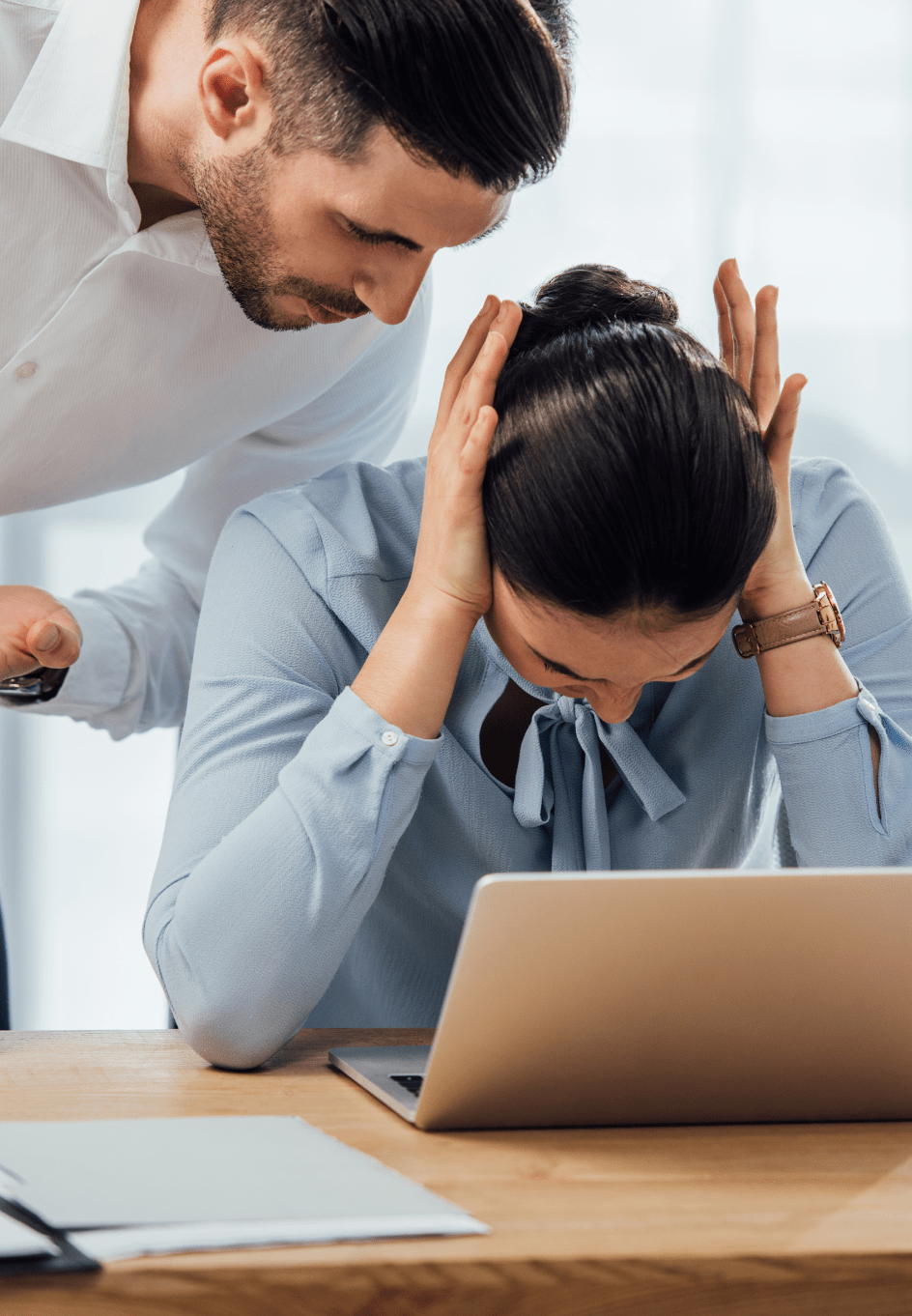

- Harassment / Bullying

- Independent Contractors

- Just Cause For Termination

- Lay-Offs

- Non-Competition / Non-Solicitation

- Professional Regulation

- Severance Review / Negotiation

- Union / Labour Law

- Workplace Investigations

- Wrongful Dismissal / Unjust Dismissal

- About

- Our Team

- Blog

- Call Now: 587-391-7601

- Contact Us

“Shop Talk” Not An Excuse: Sexual Harassment Found

Holmes v Waiward Construction Management Inc., 2021 AHRC 147 is a new Alberta Human Rights case involving a female complainant who was sexually harassed at a construction site, and shortly thereafter complained and then was denied a promotion and had her employment terminated.

The Alberta Human Rights Tribunal awarded her $20,000 in damages for pain and suffering, but decided that the denied promotion and termination of employment were not themselves discriminatory, and declined to award lost wages.

This is a very interesting and informative human rights cases dealing with discrimination on the basis of gender (sexual harassment) in a contemporary workplace. The case is also very critical of so-called “shop talk” defense, which employers in industrial settings sometimes try to use to excuse unwanted sexual comments on the basis of industry culture.

Facts

The complainant was the only female employee working on a construction crew as a general labourer. Her supervisor was known to make inappropriate comments in the workplace generally. Several witnesses noted that crude comments were common at construction sites. Some specific events which occurred were as follows:

- In the lunch trailer, the employee had mentioned in conversation that she was going on a date with someone that night. The day after the date, the supervisor asked her whether she had “fucked” her date;

- One day, a random conversation in lunch trailer involved some other person who had sex with that person’s supervisor. The complainant’s supervisor then asked the complainant if she would ever “fuck her boss”. The complainant responded that she had once and it went badly;

- On another occasion, the supervisor called the complainant from his personal phone. It is unclear what was said, but it was accepted that the complainant was very uncomfortable with it;

- As the above incidents occurred, the complainant would politely try to shut down the conversation. She became more reserved and withdrawn over time, and it was found as a fact that the sexual commentary was unwanted;

- The complainant pursued a promotion. A female employee that had worked on the site longer but was new to this particular employer got the position instead;

- The complainant made a formal complaint about her supervisor’s behavior;

- Human resources started an investigation, but transferred the complainant to a different worksite on a different schedule. Shortly thereafter, the complainant’s employment was terminated for a serious safety infraction;

- The complainant advised that she had told a close friend and her boyfriend about these incidents as they occurred and that she kept a log of it because it upset her. She apparently had no medical evidence regarding the impact it had on her.

Analysis / Conclusion

The employee’s argument was essentially as follows:

- The supervisor’s comments towards her amounted to sexual harassment;

- The complainant was not given the promotion at least in part because she did not pursue a romantic relationship with her supervisor;

- Human resources did not properly investigate or handle the sexual harassment situation, instead transferring her to another site, and after the complainant’s later termination of employment, chose not to finish the investigation;

- When the employer terminated her employment, it was in part because she had recently complained about sexual harassment.

The employer’s argument was as essentially follows:

- The supervisor made crude comments, but that is common in construction and they were not as bad in that context than they otherwise would be;

- The complainant never asked the supervisor to stop, or showed any indication that she was upset;

- The complainant was only not given the job because the other candidate was a better fit for it. It had nothing to do with not pursuing a romantic relationship;

- The human resources investigation was not perfect;

- The termination of employment was due to a safety violation only, and had nothing to do with the sexual harassment complaint.

The AHRT found that the comments by the supervisor did amount to sexual harassment and that “shop talk” was not a compelling defense, noting as follows:

[50] The respondent directed much time and attention throughout the hearing to the issue of “shop talk”. In closing argument, counsel for the respondent noted that the Supervisor was “a crude man,” who spoke inappropriately and engaged in “shop talk” about sex and dating, “like at any construction site.” The very implication that sexual harassment is not sexual harassment because of the type of work location belies the fundamental principles of human rights in our province. Although some work sites may have norms that are unacceptable elsewhere, such as the use of swear words or other crude language, that does not mean we can ignore an objective baseline of appropriate behaviour that is expected in Alberta workplaces. To imply that it is “shop talk” for a male supervisor to single out his only female subordinate to ask if she “would fuck her boss” or if she “fucked” her date the night before, provides an excuse for sexual harassment to be written off as normal in the circumstances, resulting in those industries having an excuse to continue to be unwelcoming to women.

[51] […] The legislation applies whether you work in a downtown corporate setting or on an industrial worksite. If the “shop talk” of the worksite permits sexual harassment as a norm, then the employer has a human rights responsibility to change the norms. [unbderline added] A respondent employer is responsible and liable for the acts of sexual harassment committed by an employee.

The AHRT found that the promotion was given to the other candidate because she was a better fit for it and not because of discrimination. Although the complainant had been with the employer longer, the other candidate knew the site better.

The AHRT found that the employer had “completely failed” to meet its obligations respecting the sexual harassment compliant, as the investigator was unqualified, with no harassment investigation training or experience, who transferred the complainant to another site and failed to complete the investigation after the complainant was later terminated. The employer had required the supervisor to take a sexual harassment awareness course, but in the context of a purported sexual harassment it should have completed its investigation.

The AHRT found that the complainant’s employment had been terminated due to a serious safety violation in the role she was transferred to. The AHRT found that the incident occurred, and that new supervisor was unaware of the sexual harassment complaint. The AHRT declined to draw the inference that the termination of employment was related to the sexual harassment complaint.

The Alberta Human Resources Tribunal went on to find that the complainant was entitled to $20,000 in general damages for the pain and suffering this discrimination caused her.

My Take

This decision is very interesting to me for three main reasons:

- The employer tried the old “shop talk” defense and it failed (as it often does in modern cases). I cannot disagree with the AHRT analysis on this point, but having worked in industry many years ago I think the task of changing the norms of what is discussed at construction sites will be very, very challenging for employers;

- The human rights tribunal easily found that sexual harassment had occurred and that human resources failed to address it properly, but stopped short of inferring that the lack of promotion or termination of employment was related to discrimination. It all seems very coincidental to me personally, but I was not there to hear the evidence;

- The complainant apparently did not have any medical evidence to support her pain and suffering claim, but was nevertheless awarded $20,000 in that regard, which is historically quite high.

A published copy of Holmes v Waiward Construction Management Inc., 2021 AHRC 147 can be found at the following link: https://www.canlii.org/en/ab/abhrc/doc/2021/2021ahrc147/2021ahrc147.html?searchUrlHash=AAAAAQAjImh1bWFuIHJpZ2h0cyIgYW5kICJkaXNjcmltaW5hdGlvbiIAAAAAAQ&resultIndex=21

Recommended Reading

Constructive Dismissal Consultation Discrimination Employment Contracts Employment Law Severance Workplace Investigations

A Guide to Employment Lawyer Consultation in Calgary, Alberta

When facing employment issues, finding the right legal support is crucial. At Bow River Law, we offer experienced employment law…

10 July 2024